Grafting tomatoes for vigor and disease resistance

Posted on: March 4, 2020 | Written By: Doug Oster |

When Rich Gebrosky noticed grafted tomato plants in a seed catalog, it piqued his interest.

“But they were so expensive,” he says, “I decided to look into it and see if I could make my own grafted plants.”

This photo shows a grafted tomato plant. The rootstock is below and the scion above, held together initially by a grafting clip. Photo courtesy of Purdue Extension

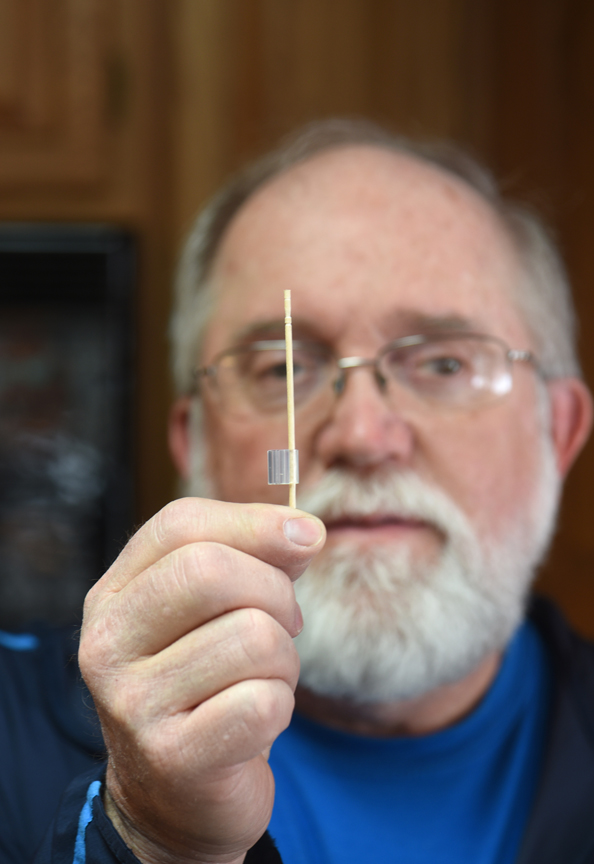

Rich Gebrosky holds a grafting clip with a small dowel rod, which acts as a stake to help support grafted tomatoes.

Grafting tomatoes starts with two sets of plants. There’s the rootstock, which has a vigorous root system but, in many cases, would produce an inedible or inferior fruit. The second, a variety known for good tomatoes, called the scion, is grafted on top of the rootstock.

The advantage of grafting is that it should create a plant that will put on more tomatoes, be disease-resistant, more tolerant of stress and have strong root system. Grafted plants basically combine the best traits of the rootstock and scion.

Gebrosky started his research online and discovered this site from Purdue Extension, which details how to graft tomatoes.

“It’s very easy to follow and has pictures, too,” he says.

The Murrysville gardener used Tomato Growers Supply to find the rootstock seed and grafting clips that are used to join the rootstock with the scion.

Last season he used ‘Estamino;’ this year he’s trying ‘Super Strong Tomato’ as the rootstock seed.

“It has a lot of disease resistance,” he says of these rootstock cultivars. “They say it helps set more fruit,” Gebrosky adds about grafting in general.

Grafting process

Last year he used ‘Roma’ as the scion, and started the seed at the same time indoors as ‘Estamino,’ the rootstock seed.

When the plants were three to four inches tall, he used an old-fashioned razor blade to cut the top of the rootstock plant off just above the cotyledon leaves (the first to appear on the plant when it sprouts) at about a 45 degree angle. The same was done to the top of the scion, which was cut just below the first true leaves. Gerbrosky used a piece of poster board with the 45-degree mark as a template to assure the rootstock and scion were perfectly matched. This is critical for the process to work.

“The better you make that fit, the more likely it will take,” he added.

The scion is placed on top of the rootstock and then a transparent plastic grafting clip is attached to hold the two plants together. Being able to see through the clip allows for the perfect union between rootstock and scion. He also uses a thin dowel rod on the clip, which acts as a tiny stake, helping support the plant as the graft heals.

The plants are placed into the dark, inside a plastic tote for three to four days and then are misted with water a few times a day to keep humidity up.

“I guess that’s to help with the shock of being cut in half and being put back together,” Gebrosky says laughing.

He slowly acclimated the plants to the light over a week, getting 11 of the 12 grafted plants to take.

“It was actually pretty easy, to be honest with you,” he says.

When planting out, it’s important to keep the graft union above ground, to get the benefits of the grafting process.

Grafting success

He planted non-grafted ‘Roma’ tomatoes next to grafted versions and saw a marked contrast in the plants.

“There really was a difference,” he says. “There were more tomatoes on the grafted plants.”

At the end of the season, when he pulled up the spent vines, the grafted plants stood out.

“It was incredible the difference in the root system,” he says. “The roots were three feet long and had branched out in every direction; they were hard to pull out.”

His first grafting experiment was a success.

“I was really happy that they worked and kind of proud that 11 out of 12 made it,” he says. “Last year I had some of the best tomatoes I’ve had in 10 years.”

This year he’s taking what he’s learned and trying some new things. He’ll wait until the initial plants are bigger, about six inches high, and he’s trying a few different varieties as the scion. ‘Rutgers’ has always been one of his favorites, and he’ll also try ‘German Johnson’ and maybe some red and yellow pear tomatoes, too.

“I told the neighbors,” he says about his project. “I’m hoping to have enough so I can give them away this year.”

Another convert

Mike Flynn grew these two ‘Better Boy’ tomato plants side by side. The smaller plant on the left was a conventional plant, the larger on the right was a grafted variety.

Mike Flynn of Moon saw grafted tomato plants in the Seeds and Such catalog and felt the same way Gebrosky did about the cost. He used ‘Maxifort’ as the rootstock from Johnny’s Selected Seeds, using his favorites, ‘Big Boy,’ ‘Early Girl,’ ‘Better Boy’ and ‘Fourth of July’ as the scions.

He was only able to get four or five to complete the grafting process, but he saw great results from the plants in the garden. In a side-by-side comparison with a non-grafted ‘Early Girl,’ he saw the same difference Gebrosky did.

“It was stronger, taller and it produced more tomatoes,” Flynn says of the grafted ‘Early Girl’ plant.

He followed most of the same procedures as Gebrosky, but instead of using a 45 degree cut, he cut the plants straight across and stacked the scion on top of the rootstock. The timing must be right on the cuts, so that the stem matches the size of the grafting clips.

“After a day or two, you can see which ones are going to make it,” Flynn adds.

Both gardeners like to get their tomato seeds started in mid-March, and Flynn has even been able to pick his early varieties in June.

“You want stronger plants, you want plants that are more disease-resistant,” he says of grafting.

“I’m sold on it,” he adds about the process. “It’s a little more work, but once you get them going, the rewards are worth it.”

Doug Oster is editor of Everybody Gardens, a website operated by 535Media, LLC. Reach him at 412-965-3278 or doster@535mediallc.com. See other stories, videos, blogs, tips and more at everybodygardens.com.

More from Everybody Gardens

Growing disease free tomatoes.

This heirloom tomato has an amazing story of resilience.

How to grow garlic for five different harvests.